7 species (kinds) of penguin live In Antarctica

They build nests there

Emperor penguins are the largest penguins

Adelie penguins are the smallest Antarctic penguins

The only land animals that live in Antarctica are penguins.

Adelie penguins

Adelie Penguins are the smallest of the Antarctic penguins, about 70 cm tall and 5.5 kgs in weight. Their main predators in the sea are leopard seals, which often lie in wait beneath rock ledges to grab the first penguin into the water. Their main predators on land are skuas, birds that break and eat the eggs, or prey on the small chicks. They come ashore in October to breed in the few weeks of summer.

Adelie penguins: the smallest Antarctic penguins © Getty Images

There is fierce competition for nest sites on high ground in the middle of the colony where it is safer from skuas. Soon after laying 2 eggs in a rocky nest, the female returns to the sea to feed, leaving the male for up to ten days. Nests cannot be left unattended in the intense cold, so males and females take turns incubating the eggs. After 30 days the chicks hatch, and parents take turns to feed them. At 4 weeks old, they are as big as adults and both parents must hunt together to get enough food to feed them. The colony’s chicks wait together in the care of a few adults. Adult birds gather in large numbers at the water’s edge waiting for the right moment to take the plunge. There are about 2.5 million Adelies in Antarctica.

Gentoo Penguins

Gentoo penguins travel further than other penguins to find food. © Getty Images

Gentoo penguins have the biggest range of any penguin, spreading over Antarctic coastal islands and islands further away. They can dive to about 330 metres, but generally feed closer to the surface. They breed on Antarctica and on the islands nearby in September- October. Females lay 2 eggs, the second one about 3 days after the first. Chicks hatch about 35-40 days later. They are the largest of the brush-tailed penguins, about 75 cm tall and 5.5 kg in weight.

Chinstrap penguins

Millions of Chinstrap penguins live in Antarctica. © Getty Images

The Chinstrap penguins are named for the narrow band of black feathers extending from ear to ear under their chins. They are about 71 – 76 cm tall and weigh about 4.5 kg and are the most numerous of penguins, with a population of about 12-13 million, found only on the Antarctic Peninsula and the sub-Antarctic islands. They nest in high places that are the first to become free of snow so that their chicks have more time in which to mature.

Rockhopper penguins

Rockhopper penguins have yellow feathers on their heads. © Getty Images

Crested penguins have a crest of yellow feathers on their heads.

Rockhopper penguins are the smallest of the crested penguins. They weigh about two and a half kilograms.

Rockhopper penguins do not breed further south than Heard Island, which is in the mid-South Atlantic between South America and Australia. Pairs generally return to the same nest each year in October. Females lay 2 eggs, and stay incubating the eggs while the males go to sea to feed. The males and females then swap over, and the females return as the chicks hatch. The males guard the chicks and the females feed them. When the chicks are bigger, it takes both parents to find enough food for them so the chicks are left together in a group. The penguins leave the nesting island in late April.

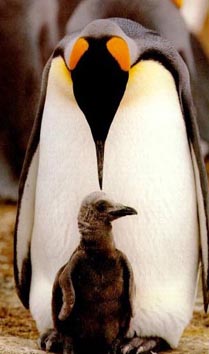

King penguins

King penguins are the second largest penguin species.

King penguins must guard their chicks from predators such as leopard seals. © Getty Images

They stand 85-95cm tall and weighing 14-16 kg. They breed on South Georgia, Macquarie and Heard islands in colonies of just 30 to thousands of birds. They prefer level ground close to the sea, on beaches and valleys free from ice and snow.

Predators at sea include leopard seals and killer whales. Main predators on land are skuas, sheathbills and giant petrels that take eggs and young chicks.

Chicks remain in colonies all year, and the adults return to feed them at irregular intervals all winter.

Royal and Macaroni penguins

Royal and macaroni penguins are very similar, with very few differences.

Scientists have only recently decided they are actually different species.

Royal penguin © Getty Images

Royal penguins have a white chin. Macaroni penguins have a black chin.

Royal penguins breed only on Macquarie Island, nowhere else in the world. They form large colonies, the largest of which consists of about 500,000 pairs!

Macaroni penguins breed on Heard and South Georgia Islands and a few others.

The females lay two eggs, the first of which is always discarded, for reasons that are not yet known. Eggs are laid in October, and hatch about 30 days later. Males guard chicks for 3-4 weeks, then both parents have to feed the chicks, who remain in groups called creches. It is not known where Royal penguins go between breeding seasons.

Emperor penguins

The Emperor penguin is the largest of the 17 different kinds of penguin.

It stands at just over 1 metre tall and is up to 30 kg in weight. Males and females look very similar, with black cap, blue-grey neck, orange ear-patches and bills and yellow breasts. Emperor penguins live and breed in Antarctica, where there is little or no shelter, at the coldest time of the coldest, most severe winter in the world.

Protection against the cold

To protect them from the cold they have a thick layer of fat under their skin, a dense layer of woolly down (fluffy feathers) and a layer of waterproof outer feathers. Only the strongest winds ruffle these feathers. Small flippers and bill help them conserve body warmth.

Other adaptations are special nostrils so they don’t lose warmth when they breathe out and a circulation system that recycles body heat. Emperor penguins stand, which leaves just a small part of the body in contact with the icy ground. They are not active through the deepest part of winter, and huddle together for warmth.

Emperor penguins. The largest of the Antarctic penguins. © Getty Images

Emperor penguins can dive more than 300 metres deep, and stay underwater for up to 20 minutes. They travel at speed by ‘porpoising’, or leaping in and out of the water like dolphins without having to change their breathing. On land they do not walk well, but waddle. Whenever they can, they slide on their bellies.

Emperor penguins spend summer feeding and gaining fat to last them through the breeding season. They assemble early in winter at breeding areas, shortly after the Antarctic sea ice has started to form. Unless one of the pair has died during the year, each penguin returns to the same partner. By the time the sea has frozen during the severe winter, the colonies may be up to 100 kms away from open sea.

Eggs are laid in winter, May – June, so that by the time the chicks hatch and grow it is the time when there is most food. Each female lays just one egg because it is too difficult to rear more than one chick in such a harsh environment. As soon as the female lays her egg, she passes it to the male who incubates it. The female travels across the ice to spend the winter feeding at sea. She must feed heavily so when she returns she will be able to feed a hungry chick. The male incubates the egg, positioning it on top of his feet so it doesn’t touch the frozen ground, covering it with a specially warm fold of his skin and feathers, called a brood patch. Incubation takes nearly two months, during which time he does not feed. During the long sunless Antarctic winter, the males huddle together, sleeping to conserve energy because they are not feeding. They take it in turns to be in the middle of the huddle where it is warmer. In temperatures lower than -60ºC with winds of 180km per hour, the temperature in the centre of these huddles can be 20°C higher.

Emperor penguin chick protected by the male's warm brood patch. Getty Images

Chicks hatch out of the eggs in early September, the beginning of spring, and stay in the protective warmth of the male’s brood patch. Females return in spring to change places with their mates, by which time the males have lost about one third of their body weight. The adults find each other by recognising their own distinctive call. The chick is moved from the father’s feet to the mother’s. The move must be completed very quickly or the chick will die in the extreme cold. The males must now travel up to 100 km across the ice to reach the open sea in order to feed.

Adults feed only their own chicks, recognising its distinctive call. Once they are about 7 weeks old, chicks join together in a crèche protected by a few adults. The chicks huddle together for warmth. They cannot swim until they have shed their down and have grown their waterproof feathers. By midsummer, they are independent and can look after themselves.

Emperor penguins can live more than 20 years, but many chicks do not survive. Large birds prey on eggs and chicks, and later when they go to sea, orca whales and leopard seals prey on them. If they survive long enough, they are ready to breed at 4-8 years of age.